Data Formats in Data Science#

Once we understand how data is described and how it is organized, the next layer to consider is how data is formatted for storage, transport, and consumption by tools. Formats determine how information is encoded on disk, how it moves between systems, and how efficiently it can be parsed or processed.

Different formats are optimized for different tasks: tabular data favors simple delimiters, hierarchical data favors nested keys, documents favor markup, and rich media requires specialized encoding. Understanding formats is essential for working with modern data pipelines.

These structural categories map naturally to different file formats used in practice:

Structured → CSV, SQL tables

Semi-structured → JSON, XML, HTML, logs

Unstructured → JPEG, MP3, MP4, PDF, TIFF

The choice of format influences the tools we use, the complexity of data cleaning, and the computational effort required to extract meaningful information.

(I) CSV and TSV#

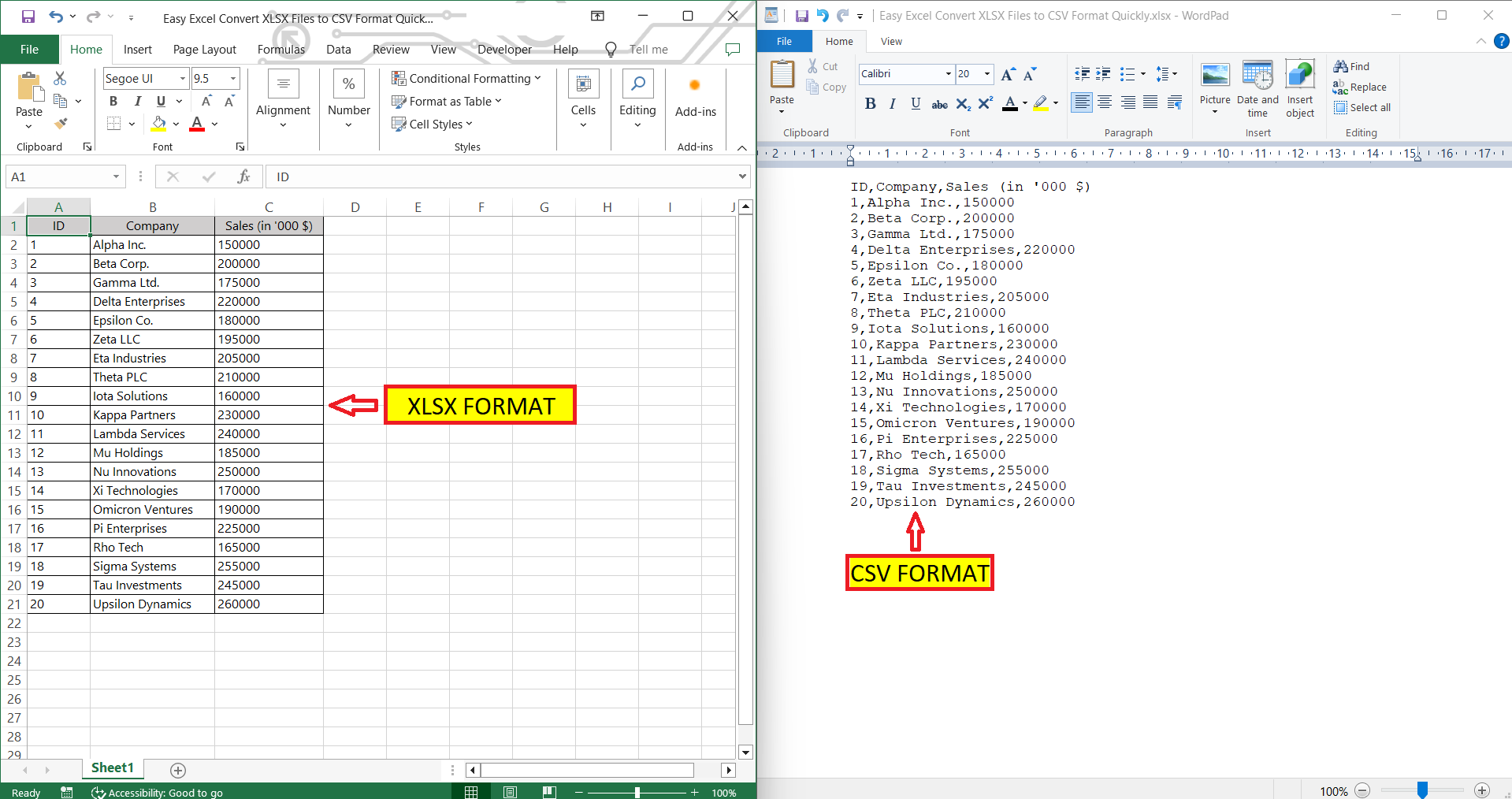

CSV (Comma-Separated Values) and TSV (Tab-Separated Values) are among the simplest and most widely used data formats. They store tabular, structured data in plain text, where each row represents a record and each column corresponds to a field.

A delimiter is the character that separates values in a row. Common delimiters include commas (

,), tabs (\t), semicolons (;), and colons (:).

CSV uses commas as the delimiter; commonly used for tabular data. It is popular because it is lightweight, human-readable, and compatible with nearly every data analysis tool, from Excel to Python’s pandas. Example CSV snippet:

Figure 9. Example workflow showing how spreadsheet formats such as Excel (XLSX) can be converted to CSV for use in data processing. Source: myexcelonline.com

Python makes CSV loading straightforward:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv("data.csv")

TSV uses tabs instead of commas, often improving readability when fields contain commas.

These formats are ideal for data exchange and quick inspection, but lack explicit typing, indexing, and schema validation.

(II) JSON#

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) represents semi-structured, hierarchical data. It supports nesting, arrays, and variable-length fields, making it flexible for web APIs, mobile applications, and configuration data.

JSON structures are built from key–value pairs, where each key identifies a field and each value holds the associated data.

JSON Syntax Basics#

At the smallest level, JSON data is expressed as a key–value pair: JSON follows a small set of structural rules:

Data is presented in key/value pairs.

Data elements are separated by commas.

Curly brackets {} determine objects.

Objects are enclosed in

{ }and contain key–value pairs

Square brackets [] designate arrays.

Arrays are enclosed in

[ ]and hold ordered lists

Keys are strings: sequences of characters surrounded by quotation marks.

Values may be strings, numbers, booleans, arrays, objects, or

null

Remember, A colon is placed between each key and value, with a comma separating pairs. Both components are held in quotation marks. As a result, JSON object literal syntax looks like this:

{“key”:”value”,”key”:”value”,”key”:”value”.}

Example JSON snippet:

{"name": "Alice", "age": 24, "languages": ["Python", "SQL"]}

JSON also supports nesting through objects and arrays. For example:

{

"name": "Alice",

"age": 24,

"languages": ["Python", "SQL"],

"education": {

"degree": "BS",

"major": "Computer Science",

"year": 2025

}

}

{

"students":[

{"firstName":"Tom", "lastName":"Jackson"},

{"firstName":"Linda", "lastName":"Garner"},

{"firstName":"Adam", "lastName":"Cooper"}

]

}

JSON is human-readable, self-describing, and machine-friendly. Most modern RESTful APIs return data in JSON.

In Python, the json module is commonly used to work with JSON data.

We use json.dumps() to convert Python objects to JSON format and json.loads() to convert JSON data back to Python objects.

Example:

import json

# Python object (dict)

person = {

"name": "Alice",

"age": 24,

"languages": ["Python", "SQL"]

}

# Convert to JSON string

json_str = json.dumps(person)

print(json_str)

# Convert back to Python object

person_back = json.loads(json_str)

print(person_back["languages"])

(III) HTML and XML#

HTML (HyperText Markup Language) and XML (eXtensible Markup Language) are markup languages that describe structure using tags.

HTML (HyperText Markup Language) describes the structure and display of web pages. It defines elements such as headings, paragraphs, links, and tables. HTML focuses on presentation and is interpreted by web browsers.

Example HTML snippet:

<p>Hello, world!</p>

<a href="https://umd.edu">Visit UMD</a>

HTML is not intended to store arbitrary data for computation. Instead, it tells browsers how content should appear and how users interact with it.

XML (eXtensible Markup Language) uses tags to describe data and relationships rather than presentation. Unlike HTML, XML does not have predefined tags. Users may define their own custom tags, which makes XML flexible for representing custom structures and domain-specific information.

XML is self-describing, hierarchical, and can represent nested structures similar to JSON.

XML is often used for data storage or exchange, especially in enterprise systems, configuration files, and legacy APIs.

Example XML snippet:

<person>

<name>Alice</name>

<age>24</age>

<languages>

<language>Python</language>

<language>SQL</language>

</languages>

</person>

XML values are contained inside tags, and fields can repeat or nest, which gives XML flexibility for representing structured documents.

HTML is primarily for presentation, while XML is more general-purpose and can encode hierarchical data for communication between systems.

Where They Appear

HTML → browsers, webpages, crawlers, scraping

XML → configuration files, enterprise systems, legacy APIs, document formats (e.g., DOCX uses XML internally)

JSON → REST APIs, mobile apps, NoSQL databases, log formats

All three formats belong to the broader landscape of semi-structured data, sitting between rigid tables and free-form text.

(IV) Relational Databases#

Relational databases store data in a structured form using tables (rows and columns) and a well-defined schema. Each table represents an entity (e.g., students, courses, orders), and each row represents a record. Tables can be linked through keys, allowing meaningful relationships to be expressed and queried efficiently.

Relational formats enforce consistency through datatypes, primary keys, foreign keys, and constraints. They excel in transactional systems (e.g., banking, e-commerce, logistics).

Why “Relational”?#

The term relational comes from mathematics: each table is a relation, each row is a tuple, and each column is an attribute. Tables become powerful when they are related to one another through shared keys.

These relationships allow us to combine information across tables (e.g., students ↔ courses ↔ enrollments) without duplicating data across the system.

Keys: Linking Information#

Relational databases rely on two important types of keys:

A primary key uniquely identifies a row within a table (e.g.,

student_id).A foreign key references a primary key in another table, creating a relationship.

Example (conceptual):

students(id)is the primary key for students.enrollments(student_id)is a foreign key pointing back tostudents(id).

Keys enforce consistency and prevent invalid references (e.g., enrolling a student that does not exist).

What is a Database Schema?#

A schema is the blueprint of the database. It defines:

what tables exist

what columns each table contains

the datatype of each column

how tables relate to one another (via keys)

rules or constraints that ensure valid data

Example schema (informal):

students(

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY,

name TEXT,

major TEXT,

year INTEGER

)

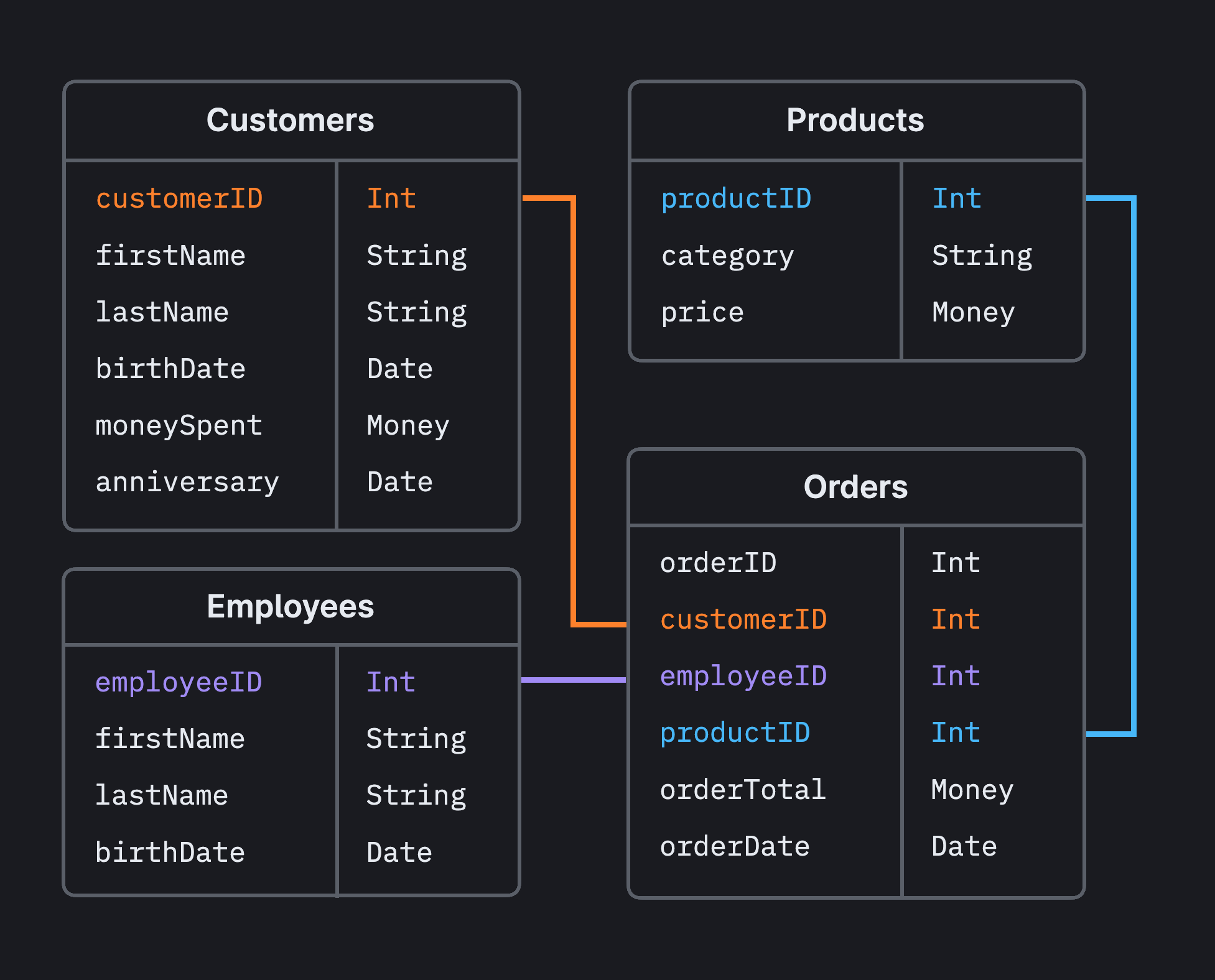

Figure 10. Relational schema showing tables linked through keys. Here, "customer_id" is a **primary key** in the `customers` table and a **foreign key** in the `orders` table, linking orders to customers. Data is stored once and referenced through keys. Source: PlanetScale

Schemas enforce consistency and make it possible to write queries that join or filter across multiple tables.

DBMS: Database Management Systems#

A DBMS (Database Management System) is software that stores, manages, and provides controlled access to databases. While a database refers to the data itself, the DBMS manages how the data is stored, retrieved, updated, indexed, and protected.

Relational DBMSs (also called RDBMS) implement the relational model and use SQL for querying. Common examples include:

PostgreSQL

MySQL

SQLite

SQL Server

Oracle

In short: the database stores the data; the DBMS manages the data.

Key idea of DBMS: applications and users never talk directly to the raw data; the DBMS sits in the middle, handling queries, security, concurrency, and storage.

Figure 11. Conceptual views of a DBMS. Both diagrams illustrate how applications interact with a database through a DBMS layer that manages queries, storage, and controlled access. Source: HBS SQL Novice Survey (top) and LinkedIn (bottom).

SQL and Querying#

The language used to interact with relational databases is SQL (Structured Query Language). SQL supports powerful operations for filtering, joining, aggregating, and updating structured data.

Relational systems enforce consistency through:

data types (integer, string, date, boolean, etc.)

primary keys (unique identifiers for rows)

foreign keys (references linking tables)

constraints (rules that maintain data integrity)

These properties make relational databases ideal for transactional systems such as banking, logistics, retail, reservations, and scientific measurement. Example Table: Students

id |

name |

major |

year |

|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Alice |

Computer Science |

2025 |

2 |

Bob |

Mathematics |

2024 |

Example SQL Query

SELECT name, major

FROM students

WHERE year = 2025;

(We will talk about SQL in later chapter)

Relational databases excel when data must be consistent, structured, and queryable, especially when multiple tables relate to each other (e.g., students ↔ courses ↔ enrollments).

They are widely used in banking systems, logistics, healthcare, retail, reservations, and scientific measurement—any domain where correctness and structure matter.

BONUS Part: NoSQL Databases#

Relational databases shine when data is highly structured and relationships are well-defined. But not all data fits neatly into tables. Modern applications produce logs, events, nested objects, user interactions, sensor streams, and media, data that grows fast and changes shape over time.

NoSQL databases relax the rigid schema of relational systems to support higher scalability and more flexible data models. Instead of enforcing a single blueprint (schema), NoSQL systems allow the structure of records to evolve.

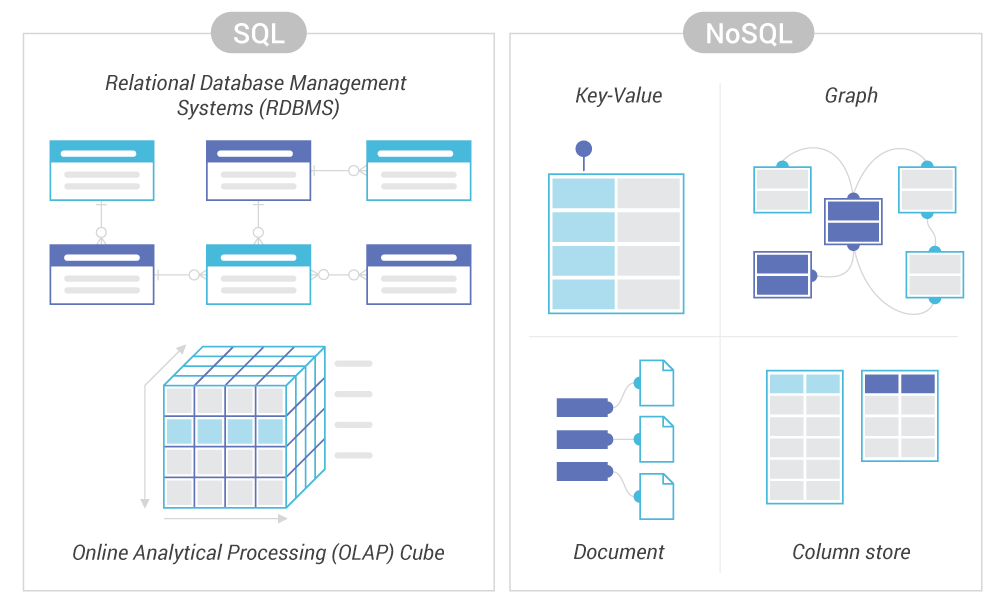

Different NoSQL databases optimize for different shapes of data:

Document stores (e.g., MongoDB, Couchbase)

Store JSON-like objects with nested fields. Great for user profiles, product catalogs, or application events.Key–value stores (e.g., Redis, DynamoDB)

Store simple (key → value) mappings. Ideal for caching, session storage, configuration, and real-time lookups.Wide column stores (e.g., Bigtable, Cassandra)

Organize data by column families. Used in time-series analytics, telemetry, and large distributed workloads.Graph databases (e.g., Neo4j)

Represent nodes and edges directly. Useful for social networks, recommendation engines, fraud detection, and biological pathways.

Figure 12. High-level comparison of relational (SQL) and non-relational (NoSQL) databases, highlighting differences in schema, consistency, and scalability. Source: ScyllaDB

NoSQL systems often target large-scale, distributed environments and are designed to scale horizontally (add more machines) rather than vertically (buy a bigger machine).

NoSQL gained popularity in the era of cloud and internet-scale platforms, where data volumes are high, latency matters, and structure is fluid. Common scenarios include:

millions of user profiles with different fields

real-time click streams and telemetry data

nested JSON returned from APIs

social networks with rich relationships

sensor and IoT data

rapidly evolving application data

In short, NoSQL trades strict relational structure for flexibility and scale. It does not replace relational databases, it complements them.

(V) Images, Audio, and Video#

Not all data is textual or numerical. Rich media formats dominate modern applications, especially in machine learning, robotics, healthcare, and online platforms.

Examples include:

Images: JPEG, PNG, TIFF

Audio: WAV, MP3, FLAC

Video: MP4, AVI, MOV

These formats encode pixels, waveforms, or frames in compressed or uncompressed forms.

How Image Data Works#

Images are typically organized as a grid of pixels, the tiny building blocks that form the picture. Each pixel holds color information through separate channels. In a standard color image:

the channels are red, green, and blue (RGB)

each channel acts like a separate layer of information

each channel value ranges from 0 to 255, representing intensity

0means no intensity (dark)255means full intensity (bright)

Figure 13. Visualization related to image data structures or pixel representation. Source: Filestack

Combining intensities across channels produces the full range of visible colors. Machine learning models (e.g., vision transformers, CNNs) operate directly on these pixel arrays and often convert them into structured embeddings for downstream tasks such as classification or detection.

Audio and video follow the same idea at higher dimensionalities: audio stores waveforms over time; video stores sequences of image frames, sometimes with sound and metadata attached.

Machine learning models for speech, vision, and multimodal data help translate these rich formats into structured forms that can be queried, compared, or used for prediction.

Choosing the Right Format#

There is no single “best” format. CSV is ideal for spreadsheets; JSON is ideal for APIs; SQL is ideal for transactions; NoSQL is ideal for flexible schemas; media formats are essential for perception tasks. Data scientists must often convert between formats depending on the application.