Introduction to Data Science#

Not too long ago, conversations about careers rarely mentioned terms like AI, Machine Learning, or Data Science. Today, those words are everywhere, on campus, from news headlines to LinkedIn posts and even in casual conversations with friends. But surprisingly few people really know what they mean. Some assume data science is just cleaning and analyzing data, and others think data science and machine learning are the same thing. While these ideas aren’t completely wrong, they leave out most of what data science actually involves.

Figure 1: Example LinkedIn job trends in AI/Data Science. Souce: LinkedIn via Ana Rivas Cano.

In reality, data science involves far more than collecting a dataset and training a model. It includes gathering data, organizing and cleaning it, exploring it to understand patterns and limitations, and transforming it into something that can support analysis or machine learning. And even after modeling, the work continues; data scientists must interpret the results, decide what matters, and communicate insights to the final stakeholder, whether that’s a client, a manager, or a team making decisions.

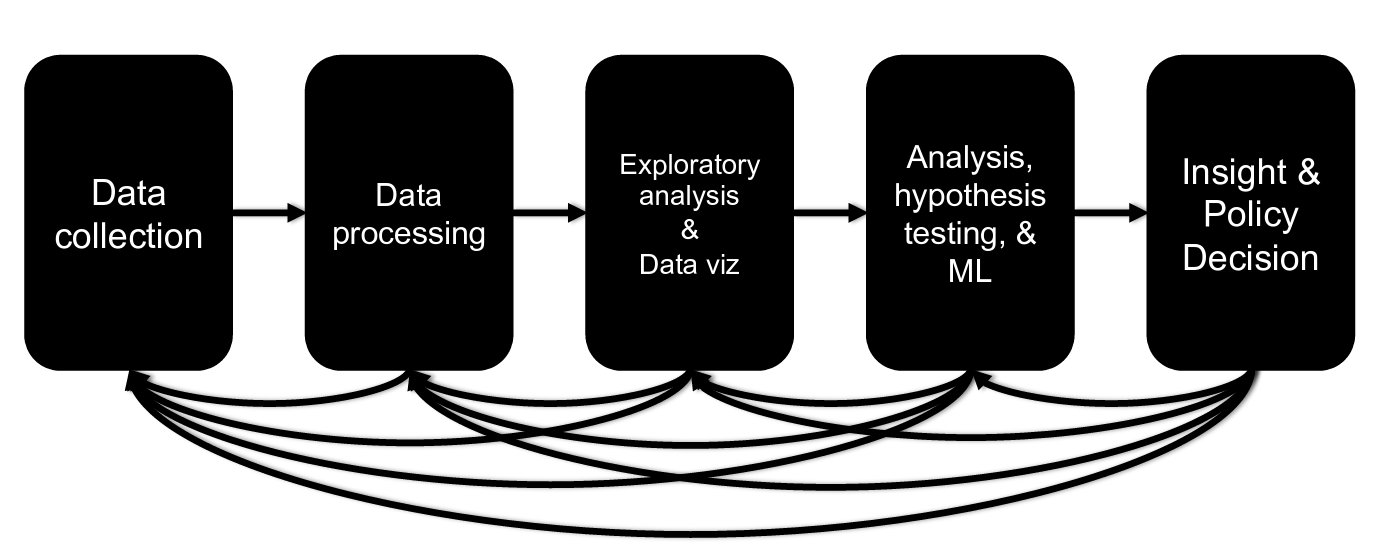

Figure 2. An illustrative example of a Data Science Life Cycle. Source: Springboard (2022).

Because of all these steps, data science follows a structured workflow often called the Data Science Life Cycle (DSLC).

Throughout this chapter and throughout the rest of the book, we’ll walk through that process in detail. But before we do that, it’s worth taking a quick look at how data science started and how the field developed into what we know today.

What is Data Science?#

Before we explore the history of the field, it is useful to pause and ask a seemingly simple question: What is data science? Although the term is widely used, its meaning depends on who is speaking and in what context. Over the last two decades, researchers, practitioners, and industry leaders have offered formal definitions that capture different facets of the discipline.

Long before the term “data science” became widespread, researchers in the KDD community were already thinking about how to extract knowledge from data stored in large databases.

KDD, which stands for Knowledge Discovery in Databases, refers to both a field of study and a process that emerged in the 1990s around the problem of discovering useful patterns and information from data.

From this perspective, Fayyad et al. (1996) defined knowledge discovery as:

“The non-trivial process of identifying valid, novel, potentially useful, and ultimately understandable patterns in data.” — Fayyad, Piatetsky-Shapiro & Smyth (1996)

A few years later, William S. Cleveland (2001) used the term data science to describe a broader vision for the field. His work offered one of the earliest modern definitions, framing data science as an extension of statistics into the era of computing and large-scale data. He described it as:

“A multidisciplinary field that uses scientific methods, data, and computation to generate insight and guide decision-making.” — William S. Cleveland (2001)

As the field moved into industry and technology companies, the definition broadened further. Mike Loukides from O’Reilly Media remarked that data science combines statistics, computing, and domain context with a practical orientation:

“Data science is about looking at data, building models, and using those models to understand the world and make decisions.” — Mike Loukides (2010)

While industry often emphasizes applications and job roles, academia has also attempted to clarify what data science fundamentally is as a discipline. A particularly influential academic treatment comes from David Donoho (Stanford University), who argued that data science is:

“The science of learning from data, with an emphasis on prediction, inference, and the extraction of knowledge.” — David Donoho, “50 Years of Data Science,” 2017

Donoho emphasized that data science sits at the intersection of statistics, computing, and domain expertise, and that its primary goal is insight; whether that insight takes the form of a prediction, a pattern, a decision, or a scientific conclusion.

Figure 3. A common Venn diagram illustrating the interdisciplinary nature of data science.

Original source: Drew Conway (2010), “The Data Science Venn Diagram.”

Similarly, machine learning researcher Zico Kolter from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) underscored the computational perspective, describing data science as:

“The application of computational and statistical techniques to gain managerial or scientific insight into real-world problems.” — Zico Kolter, Carnegie Mellon University (CMU)

Across these definitions, a consistent theme emerges: data science is not just about algorithms, programming, or statistics alone. It integrates mathematics, statistics, computation, and domain knowledge to make sense of data and support decisions in the world. Together, these perspectives show how the field bridges scientific inquiry, computational tools, and practical applications. ────────────────────────────────────────

A simple working summary#

For the purposes of this book, we will adopt a practical working summary:

Data science is an interdisciplinary field focused on discovering patterns and describing relationships in data, and on turning raw information into insight, decisions, and value.

────────────────────────────────────────

Why Data Science Matters?#

Data science matters because it turns raw data into understanding, and understanding into action. In a world filled with uncertainty and information overload, it gives us a way to navigate, reason, and make better choices.

Imagine trying to make decisions in a world overflowing with information. Every time we click, swipe, buy something, post something, or run an experiment, we leave behind tiny traces of data.

On its own, this data is just noise. What makes it useful is our ability to turn it into something meaningful.

Data science helps us do exactly that. It allows scientists to explore complex questions, businesses to make better decisions, governments to plan and respond, and organizations to understand the world around them. Sometimes the goal is to predict what might happen in the future, such as estimating customer demand or forecasting the weather. Other times, the goal is to explain why something happened or to describe patterns that were not obvious before.

In a broader sense, data science matters because it connects three important things: data, computation, and human judgment. With these tools, people and organizations can make more informed choices in a world that is increasingly shaped by data.