A Beginner’s Working Model#

Before we touch syntax, it helps to understand what Pandas adds to Python.

From Python Objects to DataFrames#

Python already has ways to represent data:

lists ([1, 2, 3])

dictionaries ({“age”: 21, “major”: “CS”})

lists of dictionaries (a common “JSON-like” pattern)

The problem is that none of these act like a table. For example, consider a list of student records:

students = [

{"name": "Alice", "year": 2025, "major": "CS"},

{"name": "Bob", "year": 2024, "major": "Math"},

]

Python can iterate through this, but asking simple questions (“which majors?”, “how many in each year?”, “filter by year”) requires loops, conditionals, and manual bookkeeping.

Pandas provides a format that behaves like a table:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame(students)

Now the same questions become natural:

df["major"].value_counts()

df[df["year"] == 2025]

This illustrates the core Pandas philosophy:

Take common data-analysis questions and make them one line instead of a small program.

Core Data Structures#

It’s tempting to think Pandas has only one object — the DataFrame — because it dominates most workflows. But understanding the smaller building block helps.

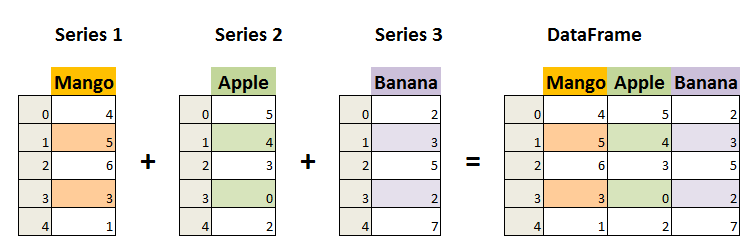

The strength of Pandas lies in two core objects:

Series: is a single column (one-dimensional labeled array)

Dataframe: a table of columns (two-dimensional labeled data structure)

People often describe the relationship like this:

A DataFrame is a collection of Series that share the same index.

That index part will matter later.

You won’t use Series much explicitly at first, but understanding it later pays off (especially for groupby, apply, or time series).

Series: The One-Dimensional Workhorse#

A Series is a one-dimensional labeled array that can hold any data type. Think of it as a single column in a spreadsheet.

Unlike some arrays that require all elements to be the same type (homogeneous), a Series can store different types of values together, such as numbers, text, or dates. Each value has a label called an index, which can be numbers, words, or timestamps, and you can use it to quickly find or select values. Here are some examples:

How to Create a Series#

A Series can be created directly from a Python list, in which case pandas automatically assigns default numeric indexes (0, 1, 2, …) to each element.

You can also create a Series from a Python dictionary, where the dictionary keys become the index labels and the dictionary values become the Series values. In Python 3.7 and later, the order of the keys is preserved, so the Series keeps the same order as the dictionary

import pandas as pd

# Creating a Series from a list

temperatures = pd.Series([22, 25, 18, 30, 27],

index=['Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri'],

name='Daily_Temps')

print(temperatures)

# Creating a Series from a Dictionary

grades = {"Math": 90, "English": 85, "Science": 95}

dict_series = pd.Series(grades)

print(dict_series)

Mon 22

Tue 25

Wed 18

Thu 30

Fri 27

Name: Daily_Temps, dtype: int64

Math 90

English 85

Science 95

dtype: int64

import pandas as pd

# Homogeneous Series (all integers)

print("Homogeneous Series \n")

homo_series = pd.Series([10, 20, 30, 40], index=['A', 'B', 'C', 'D'])

print(homo_series)

print(f"The data type is: {homo_series.dtype}\n")

# Heterogeneous Series (mix of int, float, string, bool)

print("Heterogeneous Series \n")

hetero_series = pd.Series([10, 20.5, 'hello', True])

print(hetero_series)

print(f"The data type is: {hetero_series.dtype}")

Homogeneous Series

A 10

B 20

C 30

D 40

dtype: int64

The data type is: int64

Heterogeneous Series

0 10

1 20.5

2 hello

3 True

dtype: object

The data type is: object

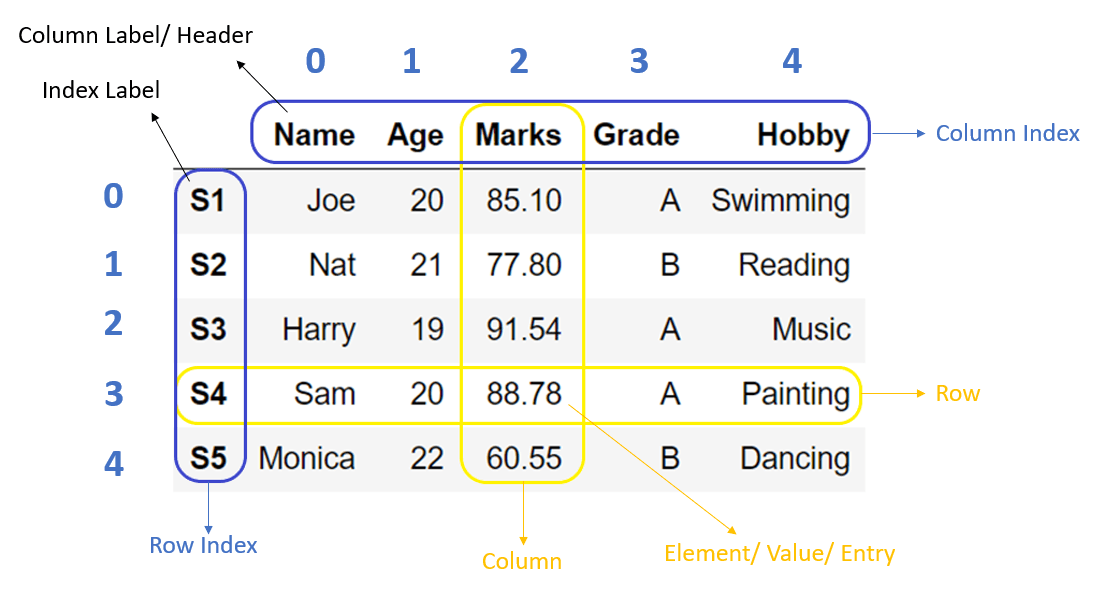

DataFrame: The Two-Dimensional Powerhouse#

A DataFrame is a two-dimensional labeled data structure, similar to a table with rows and columns. It is the most commonly used object in Pandas.

Every DataFrame has an index on the left side. In CSVs it often starts at 0 by default:

name year major

0 Alice 2025 CS

1 Bob 2024 Math

Spreadsheets also have row numbers, but Pandas treats the index as part of the data structure itself. That gives us speed, alignment, joins, slicing, and time-based operations.

Here are some examples:

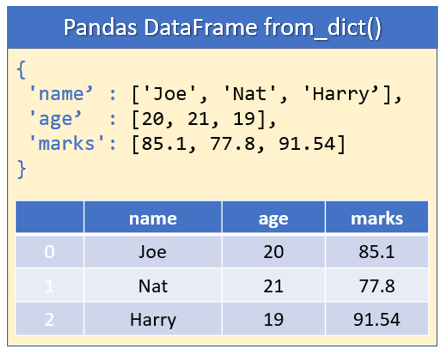

# Creating a DataFrame from a dictionary

data = {

'Name': ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie', 'Diana'],

'Age': [25, 30, 35, 28],

'City': ['New York', 'London', 'Paris', 'Tokyo']

}

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

print(df)

Name Age City

0 Alice 25 New York

1 Bob 30 London

2 Charlie 35 Paris

3 Diana 28 Tokyo

import pandas as pd

# Create a simple dataset

data = {

'Product': ['Apple', 'Banana', 'Cherry', 'Date'],

'Price': [1.20, 0.50, 3.00, 2.50],

'Stock': [45, 120, 15, 80]

}

# Create DataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Display basic information

print("Our DataFrame:")

print(df)

print("\nData types:")

print(df.dtypes)

print("\nBasic statistics:")

print(df.describe())

Our DataFrame:

Product Price Stock

0 Apple 1.2 45

1 Banana 0.5 120

2 Cherry 3.0 15

3 Date 2.5 80

Data types:

Product str

Price float64

Stock int64

dtype: object

Basic statistics:

Price Stock

count 4.00000 4.000000

mean 1.80000 65.000000

std 1.15181 45.276926

min 0.50000 15.000000

25% 1.02500 37.500000

50% 1.85000 62.500000

75% 2.62500 90.000000

max 3.00000 120.000000