(I). Measures of Location: Where Is the Center?#

If you plotted your data on a number line, where would the “center” be?

At first, this seems like a simple question, but mathematically, the answer depends on how we define what it means to be “close” to the data.

There are two main ways to define closeness:

Absolute distance → leads to the median

Squared distance → leads to the mean

Because these definitions are different, they produce different notions of “center.”

(I.a) The Arithmetic Mean#

The arithmetic mean is what most people call the “average.”

The mean minimizes the sum of squared distances:

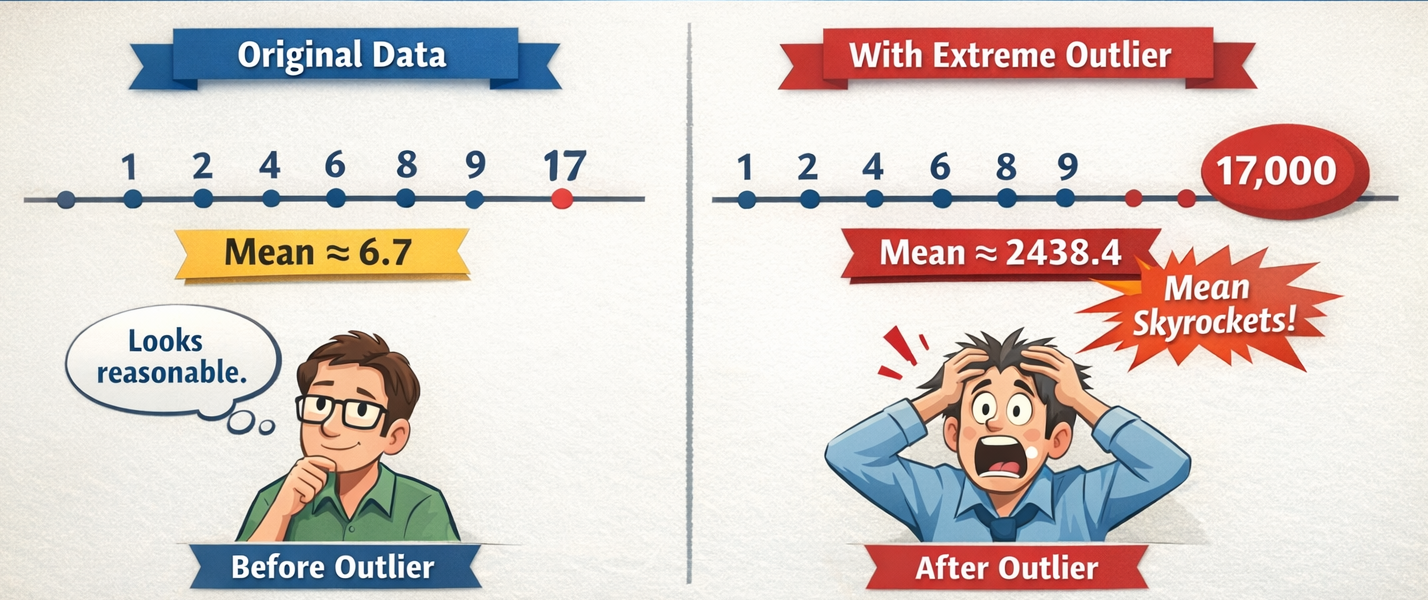

That squared term is important. Squaring makes large distances dramatically more influential.

The mean is very sensitive to extreme values (outliers).

Example:#

Figure: Replacing a single value (17 → 17000) drastically increases the mean, showing why the mean is not robust to extreme values.

The mean works well when:

Data is roughly symmetric

Outliers are meaningful (not errors)

Total magnitude matters

Example:

Average temperature

Average revenue

Average exam score in a balanced class

(I.b) The Median#

The median is the middle value after sorting the data.

If the dataset has an odd number of values → pick the middle one

If even → take the average of the two middle values

The median minimizes the sum of absolute distances:

Unlike squaring, absolute distance does not amplify extremes. So the median is robust to outliers.

Example (Income Data)#

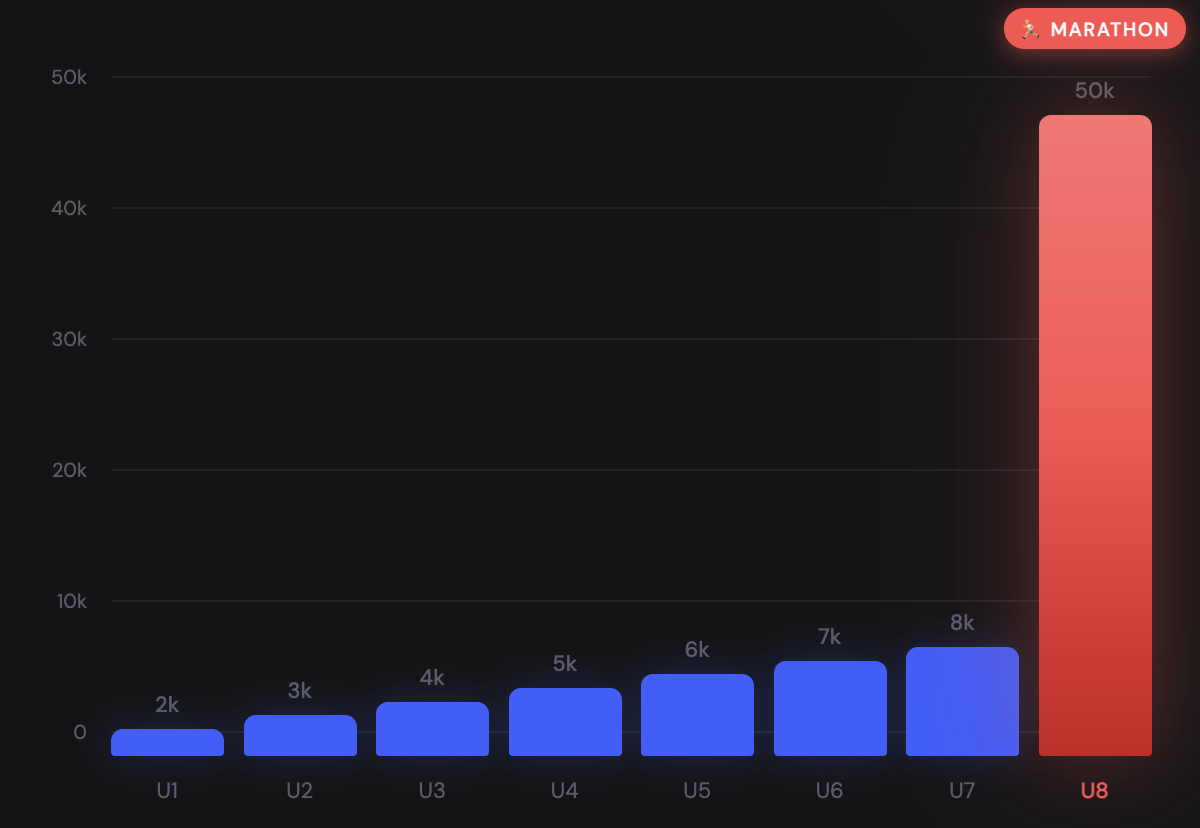

Income distributions are usually right-skewed:

Figure: Most people earn moderate incomes. A few people earn extremely high incomes

Because of this:

Mean income becomes much larger

Median income stays closer to what most people earn

So the median gives a more realistic “typical value.”

When Mean and Median Differ?#

The difference between them tells us about skewness:

Symmetric distribution → Mean ≈ Median

Right-skewed distribution → Mean > Median

Left-skewed distribution → Mean < Median

Remember: The mean reacts to the extreme values and the median resists it.

(We will revisit this idea later in the chapter.)

Weighted Mean: When All Data Points Are Not Equal#

Sometimes, observations should not contribute equally.

Example: Averaging housing prices across states.

If you ignore population size:

A small state influences the average as much as a large state.

This produces misleading conclusions.

In such cases, we use a weighted mean:

Where:

\(w_i\) = weight (population, sample size, frequency)

\(x_i\) = observation

Failing to weight appropriately can significantly distort interpretation.